The standing stones of Avebury are part of a continuous story of activity in this sacred landscape. Much trial and tribulation was had to get to the monument you see on the ground in the 21st century. It is the story of construction over a period of about 800 years, followed by two millennia of oblivion. We pick up the thread of history again in the coins Roman tourists dropped at the site, but the first mention of the stones is in 939, in a charter of Athelstan which delineated the Overton parish boundaries -

then back again to Kennet. Now this is the boundary of the pastures and downland at Mapplederlea westward. Thence northward up along the stone row, thence to the burial-places...

Prehistory and Construction

Long before the stones, before the earthwork and the avenues, the population had been building barrows and long barrows, such as those at West Kennet before 3000BC. The Coves were the first stone monuments - one at Beckhampton (one stone, Adam, now stands) and one at Avebury itself within the as yet unbuilt ring and embankment.

The Cove in Avebury

A hundred years later, construction on the Sanctuary began. This was a lovely concentric stone circle carried its evocative message through nearly five thousand years but was no match for the boorish farmer Green who destroyed it in 1724 for building stone. The Sanctuary was so completely destroyed that in 1930 Maud Cunnington had to estimate its location by retracing the exact steps of the last description of its existence by William Stukely.At a similar time the inner stone circle and the horseshoe arrangement of stones was erected, after which there was a hiatus several centuries long.

A frenzy of activity, carving out the ditch and bank took place around 2600. The great stones of the outer ring were raised around this time, followed by another pause of two hundred years. Finally, around 2400BC the avenues were added, and the majesty of Avebury was at its peak.

Intercession

Three thousand years passed - the Roman tourists saw the monument unchanged save for the tooth of Time when they dropped coins at the site. The Saxons defeated the British as Rome fell, but the earliest settlement at Avebury was a hut from around 900AD just outside the circles western entrance. The settlement grow over the next few centuries, but still lay outside the earthworks by 1200. Christianity had taken hold, and the young religion was fearful of dissent in general and Old Ways in particular, which seemed to have enjoyed a resurgence in thirteenth centuries. The sites of prehistory were obvious challenges to the authority of the Church. The Church was the next observation of the stones, when a path was agreed.

'all the way to the great old stones between the said plot and the aforesaid croft against the earthwork'

Decline

1300 was the last time anyone would see the stones intact - from then on the villagers, most likely under the instructions of the Church, began to pull down the stones and bury them. This was not done to gain fields for the plough, for the pottery excavated at the site shows no sign of repeated turning over as would have happened. The stones were the Devil's work, and had to be removed from tempting the populace to the old pagan ways. And yet the stones were treated with care - not one was smashed, they were simply lowered into pits already dug to receive them and covered over with soil.

On the south-west arc of the outer circle, a man was killed around 1320 when a stone fell on him, breaking his neck, crushing his pelvis and trapping his foot so the body could not be removed at the time. By the tools of his trade buried with him he was a travelling barber-surgeon. His death probably helped the tones, since toppling the sarsens was now associated with bad luck.

In 1349 the Black Death came to Avebury, halving the population of the village, and stone-felling ceased for a while. The people struggled the recover what was left of their lives, and the following three centuries hold little of note, until on the 7th January 1649 the young John Aubrey arrives on horseback.

John Aubrey (1626-1697)

'Avebury did as much excell Stoneheng, as a Cathedral does a Parish church'

With these words, Aubrey intrigued King Charles II, patron of the Royal Society, who demanded an explanation in person. Aubrey obliged with a rough sketch, which caught the King's imagination so that he detoured on his way to Bath to inspect the site for real. He was taken with what he saw, and instructed Aubrey to discover more. In September 1663 Aubrey surveyed the site using a plane-table to derive a plan which was to form part of his Monumenta Britannica. This was never published at the time, though an edition was published two centuries later in 1981...

Destruction

Religious zealotry once again raised its ugly head at Avebury. This time it was the most destructive Puritan form, which has erased so many historic marvels and whitewashed the richness of mediaeval church art. Aubrey came to Avebury just in time to record most of its original splendour, before the greed and small-mindedness of the nonconformist preacher John Baker who established a chapel in 1670, followed by John Bale in 1715. Their meeting house is built largely of sarsen fragments from the smashed south circle.

The village had now crept into the ring of stones, and sarsen was the nearest source of building material. Unlike the quiet piety of the 14th century stone buriers, the greed of men like Tom Robinson, John Fowler, farmer Green and Griffin fuelled by the intolerance of Puritan preaching broke up the stones by felling them and smashing them by heating with burning straw then pouring lines of cold water to fracture them. We may take at least some hear that Tom Robinson's greed was not rewarded. He was what we would now call a housing speculator, who discovered that the cost of demolishing the stones and converting them to building material was greater than the value of the houses he built. When some of them burnt down Robinson was financially ruined.

William Stukeley (1687-1765)

Stukeley, like Aubrey, was a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1719 he visited the site after reading about it in parts of the manuscript of Aubrey's Monumenta Britannica, which had been copied by an acquaintance.

He went to Avebury several times after that, drafting copious notes in great detail which have greatly helped later historians flesh out the details of Avebury's original plan after the frenzy of destruction inspired by the dreadful combination of God and Mammon. Stukeley's careful fieldwork in the early days are the only records we have of the elusive Beckhampton avenue. This was a second avenue of sarsens only confirmed by measurements between 1975 and 1989, and excavation in 1999. So eager were the stonebreakers that of two hundred stones recorded by Stukeley in Beckhampton Avenue only two are left. It is amazing that three thousand years of prehistory was so obliterated in a single boorish generation, that two hundred years later all we have left are the ghostly echoes of geophysical anomalies.

Decline Arrested

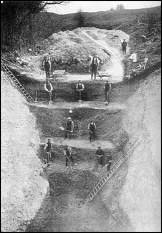

The nineteenth century brought a greater awareness of Britain's history just in time, for there were so few stones left at Avebury that the village was threatening to overrun the site. In 1872 some of the land was sold as building land, but Sir John Lubbock bought part of the village, and asked other buyers to switch their plots of others in less critical areas. Increasing interest in thing prehistoric was turned into action when the British Association for the Advancement of Science formed a committee to investigate into the age of stone circles. They commissioned Harold Gray to excavate a section of the ditch in 1908, for the princely sum of £175, which was made up to £650 with private donations. His team dug to approximately 10m below ground level before they reached undisturbed chalk. The ditch floor modern visitors see is not even half the original depth - the detritus of five hundred centuries of weathering have raised it through about seven meters.

Avebury remained vulnerable to the whim and ravages of private ownership and building speculators until 1934, with the arrival on the scene of a wealthy Scotsman.

Alexander Keiller (1889-1955)

Keiller had made his wealth in the manufacture of marmalade, but Avebury became his passion which he followed with dedication which was backed up with hard cash. In 1924 Keiller bought Windmill Hill, and by 1939 had bought up the stone circle, many of the houses in the village and some of the surrounding land. He was an energetic archaeologist, excavating Windmill Hill between 1925-29, and Avebury itself between 1935-39. Keiller was a pioneer in some areas - together with O.G.S. Crawford he published Wessex from the Air in 1928. Both men had served as airmen in the First World War and had observed how some historic features were more discernible from the air - the technique has since become a useful common tool in archaeology.

Keiller's ambition was to restore Avebury to its former glory, and as owner of the site he had the freedom to take this a long way. He re-erected many of the stones that had been buried four hundred years before, and cleared some of the more unsightly buildings and trash from the site . Modern visitors marvelling at the stupendous size of the megaliths have much to thank Keiller for, for he restored the site to as much of its former glory as was possible. The Keiller museum in Avebury tells some of this story.

In 1943 the National Trust bought the site from Keiller, they are its guardians today.